The Beauty Rules: 1960s

How beauty standards have changed over time and why we should stop paying them any mind.

“Ideal beauty is ideal because it does not exist…"

--Naomi Wolfe

Each decade or so, a new prototype ascends, bearing little resemblance to the one who came before her. The dramatically changing beauty standards are enough to give a gal whiplash.

Despite the fickle standards, putting any body shape on a pedestal (to the exclusion of others) is harmful. The subconscious yearn for society’s “stamp of approval” has dangerous implications for a woman’s achievement and personal fulfillment.

Most women experience constant self-doubt and self-ridicule related to their appearance, and worse, feel shameful for caring at all. How does this happen?

In my last blog, we began investigating this question by looking at the1950s. We learned that the preference for Marilyn Monroe and buxom pin-up girls was strongly influenced by the culture and politics of the time.

So, what was society like the following decade, and did it impact the beauty standards of the day? How were women in the sixties affected?

The decade of change

The feminists who won the right to vote near the turn of the century would scarcely recognize the subjugated women chained to housework in the 1950s.

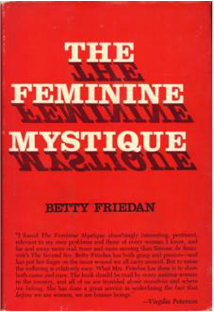

Betty Friedan was one such woman, and in 1963 she wrote a book about it. The Feminine Mystique, explored the loss of personal identity and disenchantment felt by fifties' women relegated to the home. It was a bestseller, strikinga chord with similarly unhappy females. Friedan's work was the impetus for Second Wave Feminism.

The sixties were a time of enormous cultural upheaval and transformation.

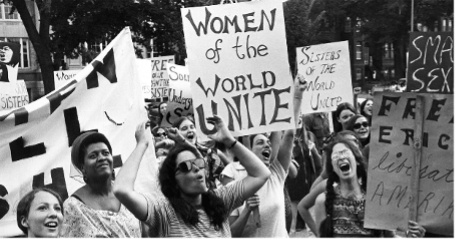

Just as women were finding their voice again, the civil rights movement was gaining steam. And as people of color fought for equality, peace-loving flower children protested the Vietnam War.

The feminists were hardly a unified front. As women from various age groups, ethnicities, and ideologieschallenged what it meant to be female, they had theoretical differences. Women of color splintered off as themovement failed to address their struggle against racism. But even the white, middle-class women couldn’t reach a consensus.

One clashing philosophy had to do with just how equal-to-men women saw themselves. Total equality, someargued, eliminates femininity. They instead believed that what makes us female is to be celebrated.

Mod and a frail bod

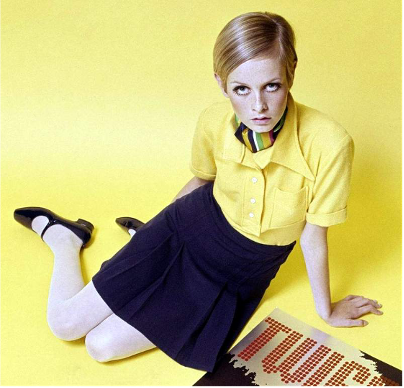

The baby boom of the 1950s meant that for the first time, close to half the American population were teenagers.Advertisers wanted a cut of the younger set's disposable income.

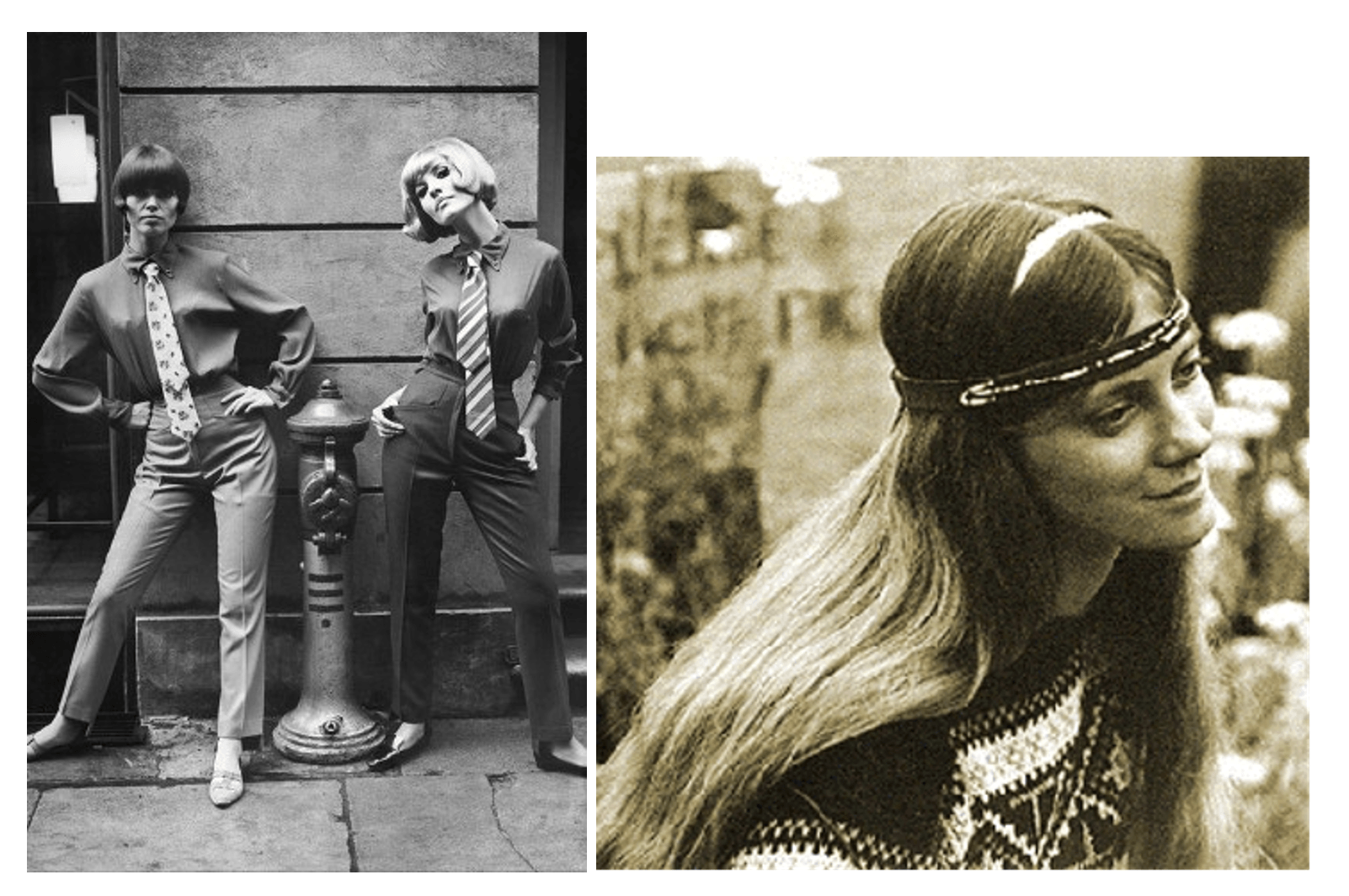

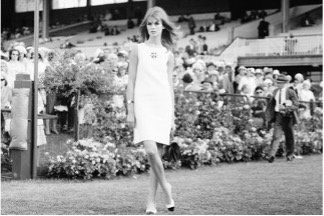

They keyed in on the rebellious spirit of teens, who wanted nothing to do with the subservient lifestyle they'd seen their mothers endure. Popular makeup

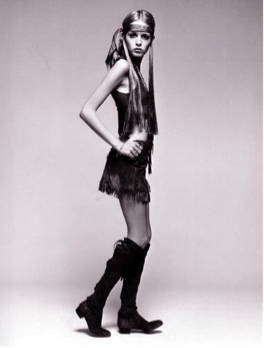

and fashion trended towards a youthful, adolescent look, ushering in models like Twiggy—a name now synonymous with a frail, almost pre-pubescent frame.

But, while women in the fifties were influenced by one standard of beauty, diversity of thought amongst activists ledto diverse beauty trends. The sixties saw fashion and makeup become a form of self-expression. You could very often identify a woman's political affiliations by her fashion sense.

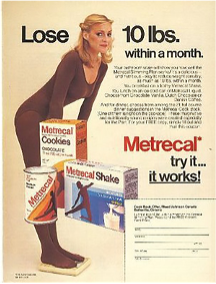

The preference for a slender figure, however, was ubiquitous. The popular press responded to Second Wave Feminism by replacing ads for household appliances with those for diet pills.

Beauty bondage endures

"What editors are obliged to appear to say that men want from women is actually what their advertisers want from women."

-Naomi Wolf

The decade that ushered in the Civil Rights Act and unfettered access to contraception was said to have set women free. But, despite tremendous strides, the pressure to discipline their bodies intensified.

The curvy, mature body worshipped in the fifties was replaced by a skinny, flat-chested,

non-threatening one. According to the popular media, the successful woman was slender with self-control.

The boom in teen culture was one influence, but the products aimed at women also changed. The hole left by cleaning gadgets needed filling, and diet and exercise aides were a frequent substitute.

Feminist writer Naomi Wolf says it's no coincidence that just as women were granted new freedoms, consumerism pushed for more control over their bodies. In her 1991 book, The Beauty Myth, Wolf describes how popular mediahelped replace the endless housework of the fifties with endless "beauty work" in the sixties.

Progressive women in the sixties would be put off by ads that suggested they be preoccupied with cleaning. Sokeeping her preoccupied with her looks was more profitable. And the ad men didn’t seem concerned with how detrimental this was to every other part of her.

According to the journal of Current Psychiatry Reports, the incidence of anorexia nervosa requiring admission to the hospital rose significantly during the 1960s and '70s, plateauing around 2012. The concept of body imagemotivating food deprivation didn't even emerge until the mid-sixties. Another coincidence?

Just as pop culture centered on youthfulness, entire industries shifted to keep up with activism, and multimedia was more accessible than ever, women were turning on their bodies in record numbers.

The same women who fought for equality in the 60s, ditched their "Mother's Little Helpers" in favor of diet pills andcigarettes. Despite all the positive social change of the decade, we hadn’t broken free from beauty rule-bondage.

X.O.

Dina B.

References:

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013. Wolf, N. (2015). The beauty myth. Vintage Classics.

hooks, bell. Aint I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Beauty, Body Image, and the Media

By Jennifer S. Mills, Amy Shannon and Jacqueline Hogue

Submitted: November 21st 2016Reviewed: April 3rd 2017Published: October 25th 2017 DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.68944

Dell'Osso, L., Abelli, M., Carpita, B., Pini, S., Castellini, G., Carmassi, C., & Ricca, V. (2016). Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa andrelationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 12, 1651–1660. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S108912