The Beauty Rules: 1970s

How beauty standards have changed over time and why we should stop paying them any mind.

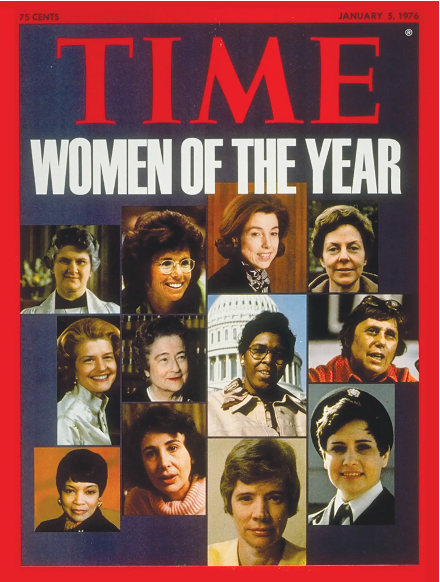

“They have arrived like a new immigrant wave in male America. They may be cops, judges, military officers, telephone linemen, cab drivers, pipefitters, editors, business executives – or mothers and housewives, but not quite the same subordinate creatures they were before.

Across the broad range of American life…1975 was not so much the Year of the Woman as the Year of the Women…”

Time (magazine), January 5, 1976

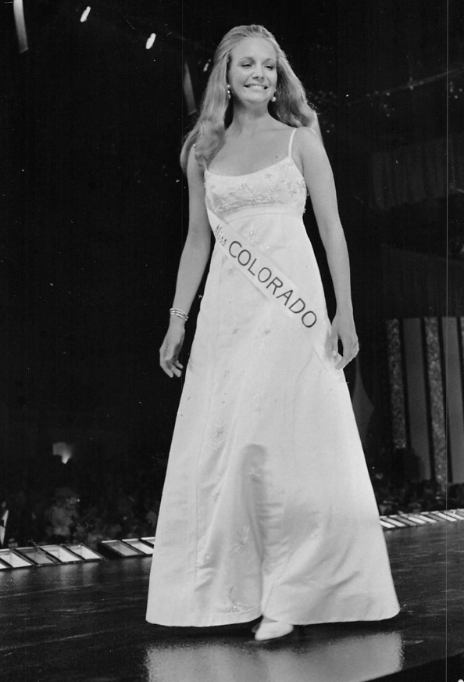

Anyone who doesn’t believe culture fosters a specific beauty “ideal” need only hear the opening line of the Miss America Theme Song, written in 1954: “There she is, Miss America. There she is, your ideal.”

But the point is already made by the existence of a “beauty pageant” at all.

We’ve been talking about beauty ideals and how societal and cultural forces play a role in shaping the decade’s celebrated silhouette. (Be sure to read my thoughts as they relate to the 1950s and 1960s.)[1]

Beauty standards have existed for seemingly all of time, despite sweeping cultural changes. But if any decade might’ve led to the extinction of beauty standards altogether, it would’ve been the 1970s. (No such luck.)

Fierce females of the 1970s

The protests of the 1960’s were just a warm up for the activists who carried the torch into the seventies. If the sixties was the decade of change, the seventies was the decade of “change faster.”

Feminism was the largest of the many social justice movements and broke from the pack with rapid progress. The fierce, fearless females back then played a huge role in changing the face of society.

Census data tells us that in 1951, 22% of married women worked outside the home. That number jumped to 68% by 1987. Previously male-dominated universities and industries finally granted access to women. Our opportunities even expanded to holding political office. But be she physician, priest, or president, many career women weren't willing to forgo motherhood.

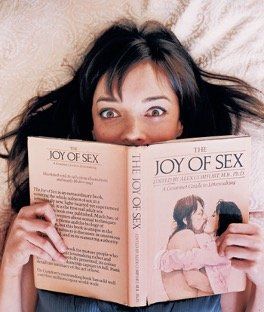

The sexual revolution

Credit feminism, greater access to the pill and abortion, or the free-wheeling, rebellious spirit of the decade, but sexual norms they were a-changin'.

A financially independent woman married later. More reliable contraception and a growing number of unmarried young adults gave rise to the single’s scene. Sex before marriage was losing its stigma.

No longer just a baby maker or vessel for her husband's pleasure, women were empowered to enjoy sex and have more of a say in the bedroom.

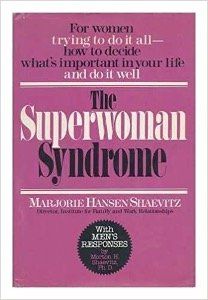

Superwoman syndrome

While feminism opened many new doors for women, it also changed what was expected of the modern woman.

By 1984, books like Marjorie Hansen Shaevitz's The Superwoman Syndrome called attention to this pressure. Shaevitz says:

"the greatest myth ever perpetrated on the modern-day woman…this type of thinking implies that all women should not only be able to do it all but that all women should want it all."

To excel at work and raise a family was more than had ever been asked of a man.

The decade of Wonder Woman

After making her first comic book appearance in the forties, DC Comics’ Wonder Woman flew into the greater cultural consciousness in 1976, as if right on cue.

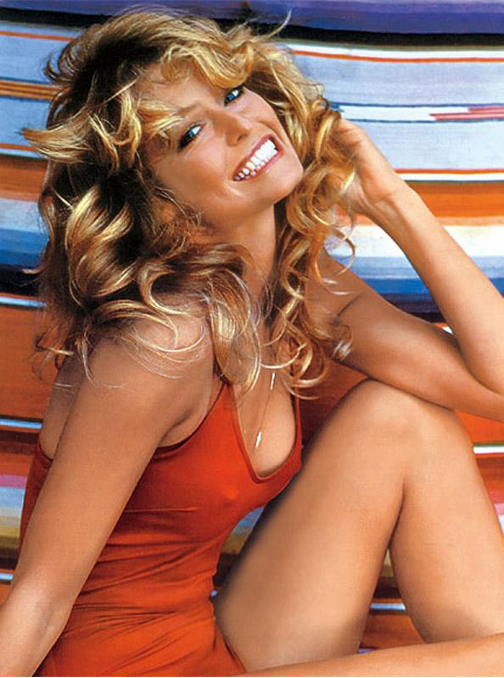

Lynda Carter was every bit the classic seventies beauty. She was taller and (slightly) more substantial than the sixties' Twiggy-type.

Muscle tone on women was having a moment. Farah Fawcett, Raquel Welch, and Jane Fonda were also more athletic than starlets from previous years.

But THIN was still very much IN.

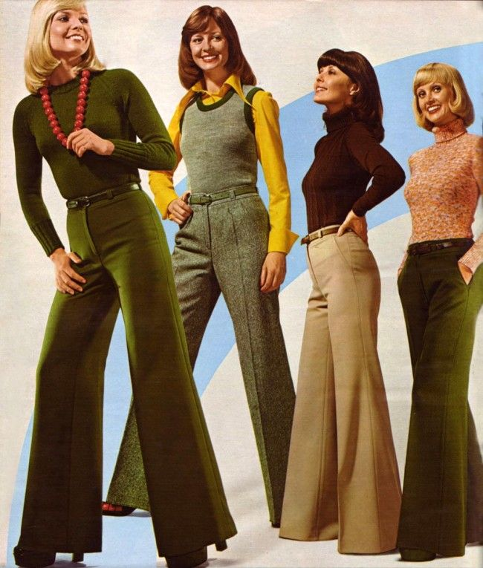

The fashions of the seventies weren't much help. Fitted Spandex and polyester fabrics were popular (and unforgiving). And women wore pants now as a general rule, leaving less to the imagination than flowy skirts. The high, tight waistline called for bodysuits since you couldn't "tuck in" and stay smooth.

In the seventies, the average American woman's BMI was around 24.9. But celebs like Morgan Fairchild and Joni Mitchell had BMIs of 18 and 20.5, respectively. The bodies society deemed most beautiful were out of reach for the average woman. Certainly without an unhealthy amount of effort.

Sadly, many women were happy to oblige.

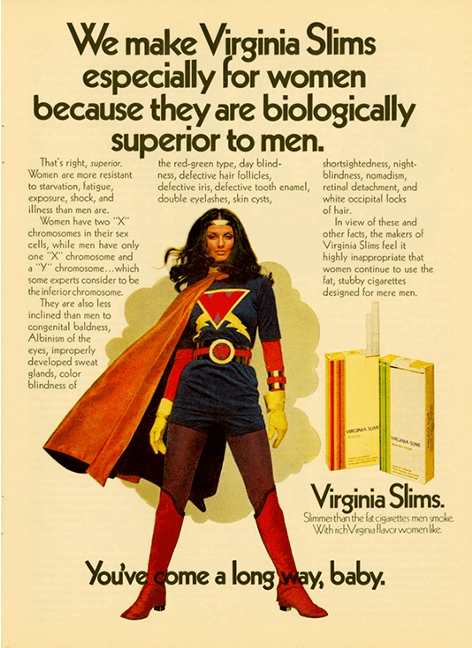

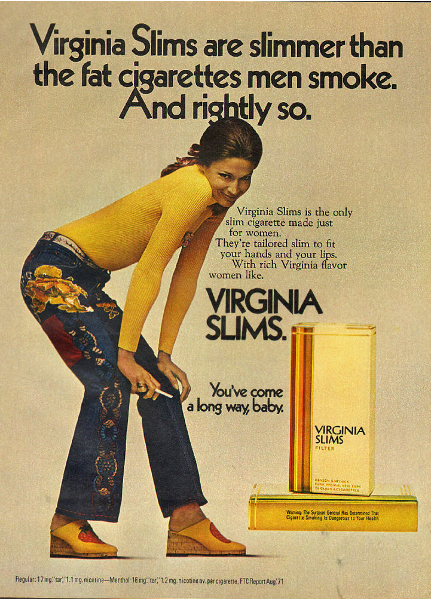

Blame the skinny starlets, the Spandex, or the singles scene, but the seventies superwoman was aware of every calorie that passed her lips. Diet pills were big business, along with fitness classes and cigarettes (often advertised as a way to keep off the pounds).

Maybe controlling her figure meant she could appear to have it all under control? If she couldn't be a superhero, she could at least try to look like one…

The downside of having it all

Feminist protests over sexist and degrading advertising spurred a giant pendulum swing. By the early eighties, women's empowerment was at the heart of almost every marketing campaign. And feminism sold! Especially as women's spending power increased.

But by asking to see a more empowered woman, feminists had inadvertently spawned another type of propaganda. In "Airbrushed Nation: The Lure and Loathing of Female's Magazines'', Jennifer Nelson blames this new trend in marketing for what she calls “superwoman complex.”

"On one hand, the [the seventies'] woman was empowered ... she was a briefcase-carrying worker outside the home. But then there was the superwoman complex that came along and meant that while she was doing all that, she was also raising kids, and she was also trying to please her man, it was like, OK women — you wanted it all, so now you can work, you can raise kids, you can look sexy and make the money."

-AirbrushedNation: The Lure and Loathing of Female's Magazines, Jennifer Nelson

The liberated woman in these new-and-improved ads was also “new-and-improved.” No longer just thin, gorgeous, and young, she was also high-achieving!

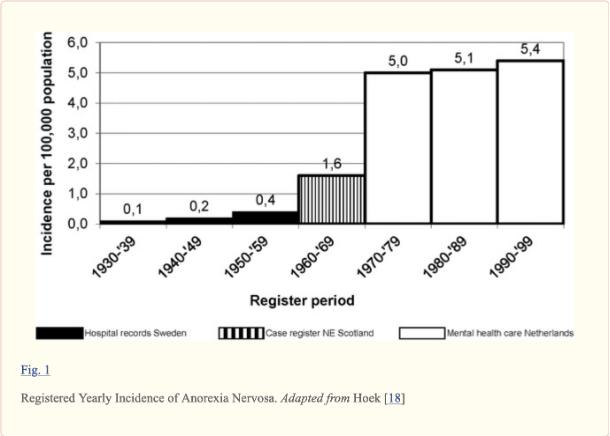

Was the renewed preference for a slim figure in the sixties and seventies to blame for the surge? Broader access to television, movies, and magazines? Were women buckling under the pressures of a rapidly changing society where their roles and responsibilities had shifted dramatically?

Before the 1970s, anorexia and bulimia were topics that only doctors and psychologists spoke about. But in 1978, a groundbreaking book was published by psychoanalyst Dr. Hilde Burch: The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa.

Hundreds of thousands of copies were sold, dragging the epidemic into the spotlight.

But nothing catapulted eating disorders into the cultural consciousness like the tragic story of Karen Carpenter. Fans looked on with concern as Carpenter grew progressively thinner through the seventies. Her 1983 death (heart failure due to anorexia nervosa) received extensive media coverage. She was 32.

Some credit increased awareness for the alarming spike in eating disorders in the seventies, believing many women suffered in silence before that.

But it IS strange that the largest spike in history happened just as women were gaining so much independence.

Naomi Wolfe, feminist author of The Beauty Myth, noticed coincidences like this. She believed there was a “beauty myth” propagated and manipulated by advertisers. Their agenda: To keep women in check.

A woman with a low self-esteem, an eating disorder, or preoccupied with her looks would find it difficult to compete with her male counterpart, goes Wolfe’s theory. And of course, that would be the point.

It’s been theorized that feminism itself is responsible for eating disorders. As offensive as that is to most women, (if you’d only stayed at home, you wouldn’t have these body image issues!) It's fascinating to try to follow the logic there.

Myth busting

Whoever is to blame for them, there seem to be two myths: the beauty myth– that a woman’s principal value is her appearance–and the superwoman myth– that success in every arena is not only possible–it’s a prerequisite.

These myths persist today, even if to a slightly lesser degree.

One of the best ways I’ve found to send these dangerous myths packing is to surround myself with a posse of inspiring AF women.

Not only do you reap the rewards of friendship, but a crew of real life wonder women reminds you:

- Not a single damn one of us is perfect.

- We’re strong as hell anyway.

- You don’t have to go it alone.

And having real-ass women in your life means you never forget what true beauty looks like.